Anti-Bias and Inclusive Candidate Profiles

In the early stages of a search, one-page summary candidate profiles are the industry standard. They are the starting point for comparing and prioritizing a long list of candidates toward a shorter list of the most promising ones to actively start contacting.

A review of global practices revealed that typically at least seven, and up to 10, pieces of information get explicitly or implicitly revealed about the candidate on these profiles (photo, name, age, nationality, location, languages spoken, educational qualifications, executive roles in reverse chronological order, non-executive roles in reverse chronological order and compensation). Both in terms of layout and content, the status quo is problematic.

On layout, most of us are trained to read from left to right and from the top to the bottom of a document. Where things appear on a page and how much attention is given to them is an active choice and does have consequences. The most crucial information about a candidate should be toward the top left of a profile. If it isn’t, it can lead to disadvantages against candidates based on information that is less relevant or irrelevant for success in a role. For example, age, nationality, location, photograph and languages spoken often appear before and above the most recent work experiences, while the latter should have the most weight.

Let’s unpack the main components of a candidate summary.

Headshot

Age

Nationality and current location

Nameless/Anonymize

Language skills

Compensation Disclosure

Education qualifications

Career history

Click on each section of the summary to learn more

What is the candidate’s headshot serving at this stage beyond encouraging biases, which could include favoring those with more conventionally agreeable and attractive features? Some might argue that showing a photograph is a convenient way to imply racial and gender diversity without having to “say it.” However, there are other, better ways to ensure diversity without resorting to photographs. Attractiveness bias is a risk at the interview stage anyway, but it is easy to avoid at this stage by withholding photographs from profiles.

Age, which is either directly recorded, as allowed in some countries, or can be easily guessed through the listed year of graduation. Whether obvious or subtle, this perpetrates the age discrimination that is rampant in senior management discussions today.

Unless it is relevant to the ability to accept a role, information regarding nationality and current location does not merit a place on the top left of a profile, and depending on the purpose they are serving, should either be left out completely or relegated to the bottom right of the layout.

There is an argument to be made for candidate profiles to be nameless/anonymized. While there may be merits to this argument, especially for entry-level, mass-recruitment roles, it is not the best solution in senior management settings unless there are strong grounds to believe that actively discriminatory factors are at play and that using names could make the situation worse. Anonymizing names in senior, more bespoke, low-volume settings can dehumanize a discussion, make it unnatural, be distracting and can crucially reduce the quality of the dialogue about the candidate between the client and the consultant.

Language skills are a legitimate line of inquiry. Both the client and the consultant should be clear on whether fluency in multiple languages is crucial to succeed in the role before including them. In any case, they are unlikely to be the most important criteria for any role and should find space only at the bottom right of the page.

Regarding compensation disclosure, data protection regulations prevent compensation information from being recorded on a candidate profile in most countries. And while this information is highly relevant to the ultimate workability of a candidate, it may not be valuable at this stage of the process. Our recommendation is that compensation details shouldn’t be included in candidate profiles, even if allowed by law. For instances where clients insist on this information, and are legally allowed to seek and record it, prudent data management will still dictate that this information ideally be communicated verbally. Recording this data in electronic communications may not be fully secure and may pose a risk that people not directly on the team can access it.

Education qualifications can to some degree signal quality (e.g., reputation of university), relevance (e.g., knowing that a candidate is a Ph.D. in a subject that is core to the client’s business), and achievement orientation from a young age. The key is ensuring they don’t receive disproportionate prominence. There is no justifiable argument for someone’s education qualifications to be placed above their recent executive career in the hierarchy of how information is conveyed or discussed. It places prominence on outcomes from two or three decades ago as compared to more recent progression and achievements. In addition, graduation years should be avoided as these are a well-trodden backdoor to approximating age.

Career history, including executive and non-executive experience, is by far the most important information about a candidate and should be clearly highlighted in the candidate profile. The reverse chronological order of the most recent experiences first and providing the location of each of these experiences is valuable and should be included. Ensuring that only the most relevant and material roles are included (irrespective of whether they elevate or hinder someone’s candidacy—a bad career decision would still classify as relevant and material) reduces clutter and improves focus. Enforcing a cut-off in visible dates for roles far back in one’s career can also be introduced to eliminate any final vestiges of age bias. For example, for all candidates across a long list, the last 20 years can be detailed more precisely, while anything beyond 20 years ago can be quoted in summary, without mentioning dates, while including basic helpful information in terms of the companies worked for, location and types of roles.

Age, which is either directly recorded, as allowed in some countries, or can be easily guessed through the listed year of graduation. Whether obvious or subtle, this perpetrates the age discrimination that is rampant in senior management discussions today.

Unless it is relevant to the ability to accept a role, information regarding nationality and current location does not merit a place on the top left of a profile, and depending on the purpose they are serving, should either be left out completely or relegated to the bottom right of the layout.

There is an argument to be made for candidate profiles to be nameless/anonymized. While there may be merits to this argument, especially for entry-level, mass-recruitment roles, it is not the best solution in senior management settings unless there are strong grounds to believe that actively discriminatory factors are at play and that using names could make the situation worse. Anonymizing names in senior, more bespoke, low-volume settings can dehumanize a discussion, make it unnatural, be distracting and can crucially reduce the quality of the dialogue about the candidate between the client and the consultant.

Language skills are a legitimate line of inquiry. Both the client and the consultant should be clear on whether fluency in multiple languages is crucial to succeed in the role before including them. In any case, they are unlikely to be the most important criteria for any role and should find space only at the bottom right of the page.

Regarding compensation disclosure, data protection regulations prevent compensation information from being recorded on a candidate profile in most countries. And while this information is highly relevant to the ultimate workability of a candidate, it may not be valuable at this stage of the process. Our recommendation is that compensation details shouldn’t be included in candidate profiles, even if allowed by law. For instances where clients insist on this information, and are legally allowed to seek and record it, prudent data management will still dictate that this information ideally be communicated verbally. Recording this data in electronic communications may not be fully secure and may pose a risk that people not directly on the team can access it.

Education qualifications can to some degree signal quality (e.g., reputation of university), relevance (e.g., knowing that a candidate is a Ph.D. in a subject that is core to the client’s business), and achievement orientation from a young age. The key is ensuring they don’t receive disproportionate prominence. There is no justifiable argument for someone’s education qualifications to be placed above their recent executive career in the hierarchy of how information is conveyed or discussed. It places prominence on outcomes from two or three decades ago as compared to more recent progression and achievements. In addition, graduation years should be avoided as these are a well-trodden backdoor to approximating age.

Career history, including executive and non-executive experience, is by far the most important information about a candidate and should be clearly highlighted in the candidate profile. The reverse chronological order of the most recent experiences first and providing the location of each of these experiences is valuable and should be included. Ensuring that only the most relevant and material roles are included (irrespective of whether they elevate or hinder someone’s candidacy—a bad career decision would still classify as relevant and material) reduces clutter and improves focus. Enforcing a cut-off in visible dates for roles far back in one’s career can also be introduced to eliminate any final vestiges of age bias. For example, for all candidates across a long list, the last 20 years can be detailed more precisely, while anything beyond 20 years ago can be quoted in summary, without mentioning dates, while including basic helpful information in terms of the companies worked for, location and types of roles.

Adjusted for all of the above, your new, improved one-page candidate profiles are largely unbiased and focus on key decision-making criteria for candidate prioritization.

Taking profiles to the next level includes bringing information from publicly available sources, complemented by data sourced with the approval of the candidate, that brings to life aspects of their diversity and lived experiences that may otherwise not be apparent or visible, but could be beneficial and differential to the client. This also helps highlight aspects of their personality and diversity that are not possible to capture otherwise in a professional experience narrative. Each candidate profile could include a personal commentary section with the understanding that these insights and information will be further enhanced during a project.

There are two caveats to this recommendation: First, depending on the nature of the personal candidate information, verbal rather than written commentary may be best, even if you have the candidate’s permission to disclose. Second, if this information is not available on everyone in the candidate slate, it can lead to inconsistencies and potential bias against those whose personal information is lacking. On balance, we’d advise including personal commentary on profiles only if it can be consistently documented without risking embarrassment or distress to anyone.

Anti-bias and inclusive client profiles

The Role of Diversity Statistics

The tracking of diversity statistics should be discussed by the client and the consultant. Progress updates should include these data on a rolling basis so their evolution can be monitored and corrected as necessary to avoid candidates falling off the radar.

At early stages, directional statistics based on logical assumptions are better than having no data, as long as assumptions are not attributed to specific candidates without their approval. As engagement with candidates deepens, assumptions must be replaced with accurate information to ensure the candidate has agreed to be considered diverse before any diversity categorization is attributed to them. This is not always immediately possible. As a result, midway through the search, the quality of diversity statistics may appear to deteriorate. This can be addressed by creating a psychologically safe space to discuss diversity and by obtaining candidate permission. If a candidate refuses or delays categorization, this does not mean they should not be interviewed or are not diverse. It is important to keep an open mind, track statistics early and regularly update them as new insights on candidates are gained.

Diversity Statistics

Expanding the Definition of ‘Lived Experiences’

“Lived experience” is intuitively understood as an individual’s story, and understanding it is a promising pathway to explore what an individual would add to the diversity of teams and organizations. It is defined as:

The firsthand or direct experiences of an individual, which give them unique knowledge, insights and perspectives that individuals who have not had those firsthand or direct experiences would typically not have.

The executive search profession and most clients are adept at exploring professional lived experiences. The need now is to expand the definition of lived experiences to cover a larger time span—from birth to today—spanning both their personal and professional life.

Getting this holistic understanding of a candidate’s personal defining moments is not easy. It takes trust and a psychologically safe environment that is built over time. While the profession (including consultants, clients and candidates) is several iterations away from embracing lived experiences in an integrative way, there is only upside to considering them as part of a search process, priming the system for greater impact over time.

The next step is understanding how those lived experiences inform the individual’s perception of the world around them, how they approach a situation, how they make decisions, form relationships and build alliances. Distilling the information on lived experiences into leadership insights around the individual is a step that could constitute the next frontier of this effort.

The final step is to appreciate the power these lived experiences will have within the setting that this new leader will enter, alongside other leaders and their own lived experiences. Without a grasp of the entirety of the lived experiences on a leadership team, it is hard to understand collective strengths and gaps, and even harder to determine when a particular aspect of someone’s lived experiences should be called upon to enhance the quality of a collective decision. Leaders already do this in terms of professional lived experiences. For example, good leaders will know which member of their team to deploy, to rely on or to seek advice from for a particular business situation. Over time, they should do this with increasing confidence on the entirety of lived experiences. That is when the true power of diversity will be unleashed for the greatest common good.

Lived Experiences

Distinctive Candidate Engagement

Top diverse talent is in exceptionally high demand, and it’s important to reflect on what makes a client distinctive and appealing to diverse candidates. Just as a company is getting to know a candidate, the candidate is learning if the company is a good fit from a career and skills perspective, and a cultural one. The situation is of course different for an internal candidate. Here, familiarity with the client and its culture may be less of an issue, although there still may be some anxiety, for example, if this is the first time a glass ceiling is being shattered at a particular level of the organization for an underrepresented minority candidate.

Seen from a client’s perspective, there needs to be recognition that simply being a net importer of diverse talent is not a viable or responsible long-term strategy. Every organization needs to play its part in the development of diverse talent pipelines of the future, and as part of that, they risk losing some of their best diverse leaders to better or faster career progression opportunities outside of the company. The cultural and reputational benefits of being regarded as an exporter of diverse talent (and not just as an importer) outweighs the short-term pain caused by the export. It is only through this collective action and the spirit shown by multiple companies that both the quality and quantity of diverse talent pipelines will change in more sustainable ways.

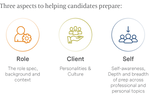

Within a search, support to all (not just diverse) candidates should broadly be in three areas:

- Positioning the role in the most honest and compelling way. This goes beyond the role specification and extends to an open discussion on the different perspectives, criticalities and trade-offs that were discussed in its making. For every candidate, knowledge of the entirety of the client objectives, including on DEI, helps frame their preparations and expectations.

- In-depth discussion both on the client’s decision-makers and on the culture. Understanding the personalities involved, their attitudes, priorities and backgrounds, makes a difference, especially to candidates who might find the characters unfamiliar. Understanding the client’s culture can help a candidate ensure that it resonates with their own personality and professional aspirations and lends itself well to a long-term stint with the company.

- Fine-tuning the interview approach. For individuals who meet the criteria on diversity, avoid overplaying the diversity elements or you risk them becoming overwhelming and one-dimensional. At the same time, don’t underplay them to the degree that they stay superficial or remain unspoken. All candidates, regardless of their background, should be prepared to discuss the full range of criteria required by the role specification and be willing to go to the depths of each criterion (including on diversity). Even for candidates who do not meet the diversity preferences, this mindset is crucial, as it allows them to share their own distinct lived experiences in a way that the client may find compelling, which may also turn out to be underrepresented in a client setting.

Candidate Engagement

Best Practice Candidate Interviewing

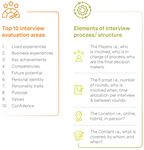

A good interview process at the senior level must cover a range of topics: personal background and lived experiences, business experiences, key achievements, competencies, future potential, identity, personality traits, purpose and confidence. Consultants should be challenged to demonstrate thorough interviewing along these lines before presenting candidates. The outcome of this consultant evaluation should be documented in a confidential report that assesses each candidate based on the agreed-upon interview topics, including concerns, gaps or areas to further probe.

The past two decades have seen an explosion in career choices and pathways that make the comparison of experiential journeys between candidates increasingly unreliable as a decision-making tool. A promising assessment is on future potential, evaluating for curiosity, insights, engagement and determination. Egon Zehnder analysis has shown this assessment to be positively correlated to future progression potential. This framework is distinct from prior work experiences and offers the possibility of equitably levelling the playing field in evaluating a diverse slate of candidates for a role. This can help avoid the vicious circle of not hiring underrepresented diverse candidates because they have insufficient prior work experience on account of being underrepresented.

Biases can occur throughout a search but may become acute during an interview process, for example, affinity bias, which favors candidates who share characteristics with the interviewers. This is not restricted to gender, ethnicity, nationality or sexual orientation. It extends to a variety of factors, including attending the same school or university, working in the same company, growing up in the same city, liking the same sports team, etc. This bias can put underrepresented candidates at a disadvantage as they are statistically less likely to share multiple characteristics with the evaluators. Underrepresented candidates may also have had life circumstances that caused them to spend a disproportionate amount of energy and time fitting into majority cultures, communities and organizations, and their formative experiences may have changed their self-image and ways of interacting with the world. It is also likely that for an equivalent position, a candidate who is underrepresented would have had to face a more challenging route to the top that ought to be factored in, demonstrating enhanced resilience or determination.

Clients can rely on a mix of “this is what I have done in the past” and “this is what I think this situation demands” to determine the content of their interview. The location of client interviews (e.g., hybrid, in person, virtual), having familiarized yourself with the candidates’ confidential report, the number of rounds, the gap between rounds, the time given to each interview, panel versus individual interviews, should different aspects be covered in different rounds, should different interviewers cover different aspects, all are pieces of the puzzle. Egon Zehnder recommends creating an interview guide linked to the role specification that provides a framework to guide the interview This guide ensures that all interviewers cover the same minimum set of questions while still allowing for interest areas of the individual interviewer. The consequences of not having a guide are that you are likely to end up with fascinating pieces of insight about a candidate, but these are unlikely to be comprehensive, consistent and in sync with the requirements of the role specification. They make it hard to calibrate the relative strengths between candidates. This creates a vacuum in which decision-making can become overly reliant on individual impressions of candidates and removed from the stated requirements of the role. It can also impact DEI outcomes and be more prone to individual biases.